The article was written special for The Dictionary of East Europe Performative Arts (the project of www.eepap.org).

Tania Arcimovič

The notion of independent theatre in the context of today’s Belarus can be approached from two perspectives. On the one hand, ʻindependentʼ means absolutely autonomous from the state, both in terms of finance (operating without the governmental support) and ideology (pursuing its own repertoire policy, operating beyond the framework of the contemporary Belarusian state ideology). A theatre company of this kind can either be overtly oppositional (Belarus Free Theatre) or refrain from expressing its civic position (Korniag Theatre, SKVO’s Dance Company, InZhest Physical Theatre).

On the other hand, ʻindependentʼ may be understood as alternative in terms of aesthetics and form. That is: using an experimental form which is uncommon in the context of state-controlled Belarusian theatre. (The notion of ʻexperimentalityʼ in this case is heavily context-dependent, because what has already become part of repertory theatre in the West, still remains experimental in Belarus.) It is not uncommon that ʻindependent theatresʼ of this type, while standing away from the official theatrical process, nonetheless receive government grants. The activity of the Centre for Belarusian Drama (CBD) affiliated with the Minsk-based Belarusian Drama Theatre is a case in point. Being a government institution, the Centre is concerned with providing support for and fostering development of the contemporary Belarusian drama, runs playwriting laboratories and organises public readings. However, not unnaturally, being aesthetically independent, it remains dependant in terms of ideology, not allowing itself any criticism of the authorities and avoiding pressing social and political problems.

THE FIRST CIRCLE. STUDIO THEATRES OF THE 1980S

The conventional starting point of independent theatre in Belarus may be set in the 1980s which witnessed the upsurge of the experimental theatrical studios movement in the country (primarily in Minsk) with dozens of projects, quite different in terms of form and ideas. Sure enough, some particular theatre productions standing out of the mainstream Soviet Belarusian theatre, dominated by psychological realism, had appeared even earlier.

Just to give an example, it is a unique fact in the history of Belarusian theatre that the celebrated play Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett was staged as early as 1968 in Minsk, for the first time in the Soviet Union (!), by the Belarusian artist Uładzimer Matrosaŭ.

It is not unnatural that the performance was met with hostility and banned shortly thereafter. (Matrosaŭ returned to Beckett in twenty years, in the late 1980s, when he founded, together with a group of professional Minsk-based actors, the Lik studio theatre). But it was the 1980s when these piecemeal one-time initiatives merged into a powerful movement to be noticed and discussed. This growth of activity was undoubtedly associated with the political processes in the country: such phenomena as perestroika, glasnost, growth of civic and national awareness contributed to changes in the theatrical process.

Starting with 1980, in Belarus there appeared in sequence unique theatre groups, both professional and amateur, which commonly operated from the premises of community centres where they found necessary rehearsal facilities. In her little monograph Studiynye teatry Belarusi 1980–1990 godov [Studio Theatres of Belarus of the 1980–1990s][1], the Belarusian theatre director and academic teacher Halina Hałkoŭskaja makes the observation that these theatrical studios started their activities mainly with exploring Western European intellectual drama (S. Beckett, E. Ionesco, S. Mrożek and others) which was unofficially banned in the USSR until perestroika. Around this time, the ban was also lifted from many Belarusian dramatic works which had been labelled by Soviet ideologists as ʻnationalisticʼ (e.g. the play Locals by Y. Kupala or works by F. Alachnovič), and stage directors started to resort to these plays to raise the issue of national self-awareness before their audience.

It was essential that every studio aspired to elaborating its own unique language. This made it possible within a decade to master diverse theatrical forms and methods, starting with conceptual issues and finishing with performance techniques.

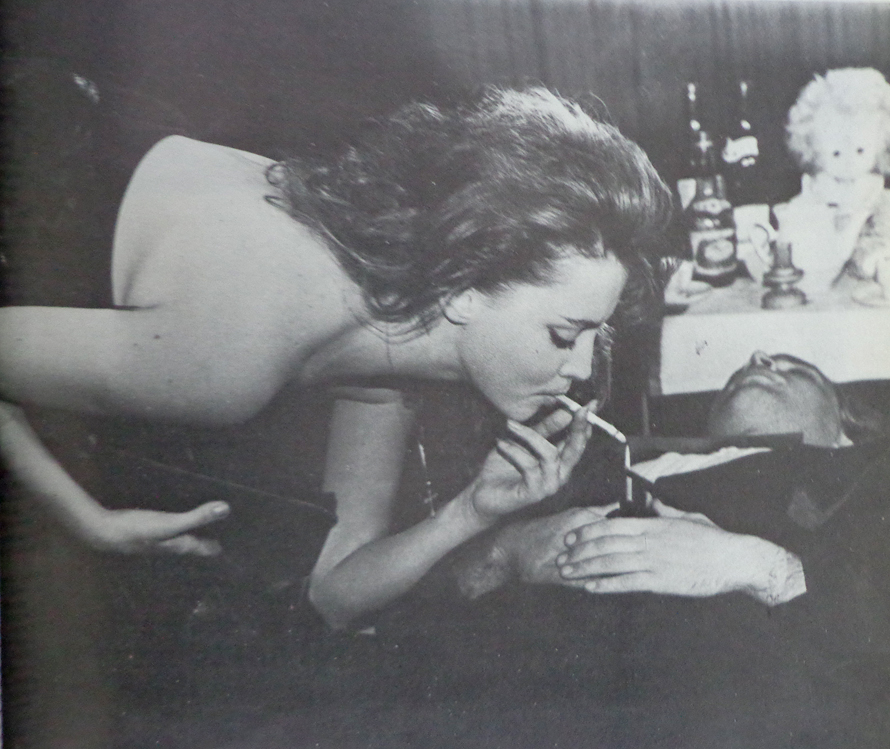

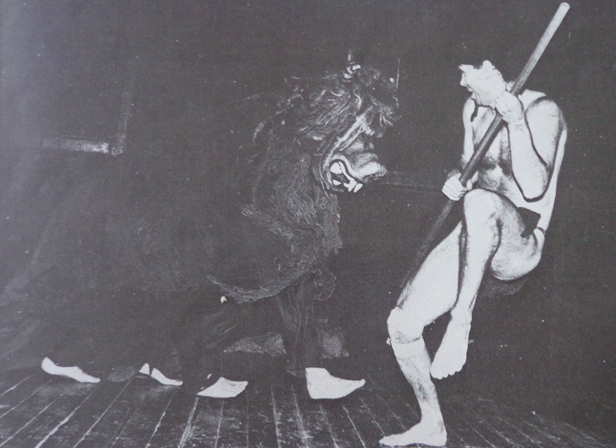

One of the most significant theatrical formations was the Gesture physical studio headed by Vyacheslav (Slava) Inozemtsev. Classic pantomime, clowning, commedia dell’arte and – later – studying the non-conventional Japanese Butoh dance made the Gesture studio unique on a national scale. Their entire creative development was a continuous state of exploration, ranging from preoccupation with the theatrical traditions of the past (street theatre, the culture of folk humour) to studying contemporary physical theatre forms. The eclecticism of the Gesture studio has become their signature style and contributed to the company’s uniqueness, not only in the Soviet Union (and later in the post-Soviet space), but also abroad. Ryd Talipaŭ, who established On the Victory Square studio in 1988, tried to implement the idea of conceptual theatre. By relying on the practice of European stage directors, Talipau merged performance and audience spaces in his productions, which was a daring innovation for the theatrical Minsk of the time. The studio gained prominence due to their performance Strip-Tease based on Sławomir Mrożek’s play known for a stylish artistic solution (which would become later Talipaŭ’s signature mark) and featuring naked bodies of the actors as the logical finale of the total psychological ʻundressingʼ of the play’s characters according to the director’s design.

The Dzie-Ja? [2] theatrical studio headed by Mikałaj Truchan and Vital Barkoŭski was another bright phenomenon of Belarusian theatrical scene. In his production of V. Seglinš’ Illusion, Barkoŭski employed the method of physical impulse theatre. In later productions staged in his own Act Studio, Barkoŭski, being influenced by the Polish director Jerzy Grotowski, extensively used the naked body, figurative signs, monotony and repetitiveness. Truchan’s performances based on F. Alachnovič’s Ghost, U. Karatkievich’s Grief and N. Gogol’s Dead Souls which he staged in the Dzie-Ja? Minsk Drama Theatre (the studio was awarded this status in 1992) became legendary in the history of Belarusian theatre. Critics emphasise the inimitable style of his productions: classical texts were boldly re-interpreted, completely submitted to the director’s plan, and became screenplays for performances on stage. Disturbing linear-time narrative, exploring archaic types of Belarusians, rethinking classical texts in the context of the day, emphasizing the bonds between the performance and its environment – these are peculiar features of Truchan’s creative work.

His performances were repeatedly included in the programme of the Edinburgh Festival (1995, 1996, and 1997) and acclaimed by English critics [3].

The theatrical studios “Dialog” (which grew later into the Alternative Theatre) headed by Vytautas Grigaliunas, “Kruh” headed by Natallia Mickievič, and “Abzac” headed by Alaksandr Markievič and Uładzimer Savicki were also known for their original theatre programmes.

In view of the growth of these studios’ popularity, not only in the Soviet Union, but also abroad, their leaders strove for official recognition of their activity which would result in these studios being provided with support including funding. In 1989, the Association of Theatrical Studios was established, which provided the auspices for several editions of the Studyjnyja Kalady Festival. All the necessary conditions were present for these studios’ experimental activity to become part of the professional Belarusian theatre scene. Most of these projects, however, have not survived due to partly economic and partly political reasons, and since the mid 1990s the theatrical studios movement has significantly declined. For the time being, Slava Inozemtsev’s project has been the only one which held true to its aesthetic values. Despite its poor material conditions and using solely its own resources, the theatre (under its new title of InZhest) not only continues to perform on the stage, but also runs a studio that provides it with its own pool of trained actors. Following the death of M. Truchan, the Dzie-Ja? Theatre has lost its one-of-a-kind vibe and is now part of Belarusian repertory theatre under the name of Novy Teatr [New Theatre].

The root problem with these companies now, however, is not that the experimental activities of these theatrical studios ceased, but that they were forgotten. Until recently, no paper had been published in Belarusian theatre studies dealing with that period.

For all the attempts to record the names of those theatre workers and to restore the chronology of their activity, it is too early to say that their experience is fully appreciated.

THE SECOND CIRCLE. THE ECHO OF EXPERIMENTS

The theatrical studios experimental movement of the 1980s, however, has influenced to a certain extent repertory theatre in the independent Belarus (especially in the pre-Lukashenko era between 1989 and 1994). This may be exemplified by the Volnaja Scena [Free Stage] Theatre-Laboratory which was founded by Valery Mazynski in 1990 and turned into the RTBD Theatre in 1993, whose objective was to support and develop contemporary national Belarusian drama. The Dzie-Ja? Studio was granted the status of Minsk Drama Theatre in 1992.

The first attempts at public staged readings of experimental foreign drama in Belarus took place in the late 1990s. The first dramatised stage readings of contemporary German plays, performed by Belarusian actors and directors, happened in February 1997 through a joint project between the Goethe Institute in Minsk and the Volnaja Scena Theatre, which resulted in the First Festival of Contemporary German-Language Drama in November 1998.

The Belarusian playwright, Prof. Siarhiej Kavaloŭ emphasised the experimental and laboratory character of this project, which provided new conditions for Belarusian directors’ activity, such as encountering another poetics, going well beyond accustomed practices, searching for alternative means of staging drama, and a different stage existence [4].

V. Mazynski, who was one of the project participants, spoke of improvisation as a basis for staged readings. It provided a unique experience for him. Now he “is not afraid of experimenting, trying to do something while not thinking about the result” [5]. Similar readings of contemporary Polish plays were held in cooperation with the Polish Institute in Minsk.

The ʻnew dramaʼ movement, which emerged in Russia in the early 1990s and amassed young authors from around the post-Soviet space, became an object of discussion in the Belarusian theatre world in the early 2000s. The almost decade-long delay on the part of Belarusian playwrights in joining the movement was primarily due to the problem of national awareness (bringing back history, the return of national heroes and affirmation of rights of the Belarusian language).

The issue of “the nation” that dominated not only the public discourse in general, but also theatrical one all through the decade following the Belarus’ national independence.

The early 1990s witnessed a boom in staging plays exploring patriotic themes. The productions of Locals by Y. Kupala and Idyll by V. Dunin-Marcinkievič (staged by M. Pinihin at the Yanka Kupala National Academic Theatre in 1990 and 1993), Like It or Lump It, One Should Kick the Bucket, and The Ghost based on F. Alachnovič’s Fears of Life and Shadow (staged by M. Truchan at the Dzie-Ja? Minsk Drama Theatre in 1996 and 1995), A.Dudaraŭ’s Duke Vytautas (staged by V. Rajeŭski at the Yanka Kupala National Academic Theatre), and others, were landmark performances of the period.

But as late as the early 2000s, a new generation of Belarusian authors and directors for whom the problem of national awareness was no less acute, joined their Russian counterparts in speaking of a crisis and stressing the necessity of changes in theatre. They acknowledged that “theatre has lost its social, ethical, and moral positions in the society. It by no means influences our life” (such was the statement made by the director Michaił Łašycki during a round table held by the Kultura weekly)[6].

Belarusian authors started to be actively engaged in the festival movement in Russia. In 2002, Andrej Kurejčyk became the Debut International Literary Award winner for his plays Blind Men Charter and Illusion, while his Piedmontese Beast won the contest organized by the Ministry for Culture of Russia and the Chekhov Moscow Art Theatre as the best contemporary play. The winning plays of the 2003 Eurasia Contest included Nicolai Khalezin’s Here I Come, Pavał Pražko’s Serpentine and Andrej Kurejčyk’s Three Giselles. The next year, Here I Come made the top ten of best plays at the All-Russian Dramatis Personae Drama Contest and won a prize at the Berlin Theatre Festival . The plays A Man, a Woman and a Firearm by Kanstancin Sciešyk and A Stage Play by Andrej Kurejčyk’s joined the winners of the Eurasia Contest. The long-list of the 2005 Eurasia Contest featured six plays by Belarusian authors including A White Angel With Black Wings, or Vain Hopes by Dzijana Bałyka; A Stage Play by Andrej Kurejčyk, And so It Is by Pavał Pražko, A Man, a Woman and a Firearm by Kanstancin Sciešyk (short-listed); White Umbrellas by Andrej Ščucki and Thanksgiving Day by Nicolai Khalezin (Kurejčyk’s and Khalezin’s plays were eventually selected to participate in the twelve-hour Theatrical Marathon on the awards presentation day). This was the widest representation of Belarusian authors in the contest’s long-list in its history. The years 2002–2004 were in fact a starting stage for contemporary Belarusian playwrights – since then, not a single Russian contest or festival has been held without them being included amongst the winners.

The appearance of new authors was accompanied by attempts to start laboratory work on new plays. One of them was the Theatre of Play project of stage readings of contemporary Belarusian plays launched in 2002 under the auspices of the Yanka Kupala National Academic Theatre and initiated by Maryna Bartnickaja, the then literary director of the theatre. The main objective of the project was to promote contemporary Belarusian drama and to interrelate playwrights and stage directors. On the one hand, as Bartnickaja noted, it was a perfect occasion to present the works of young authors to a wide audience of theatre enthusiasts, and on the other hand, it was a crash test for the new Belarusian drama. The potential of the “Theatre of Play” stemmed from the fact it did not require heavy spending. The project attracted the audience’s attention at once (the very first reading gathered full house even though admission was by ticket only), but was stopped after only a few years’ existence. The plays read under the project included A. Kurejčyk’s Piedmontese Beast, H.Cisiecki’s Silent Poet and The Web as well as the documentary play In the August of 1936 about the Belarusian national poet Yanka Kupala (directed by U. Savicki). The latter play, written by the historian Vital Skałaban, was based on NKVD interrogation protocols of the poet, which had been preserved in the archives. Maryna Bartnickaja was also the originator of the Kupalaŭskija Daliahlady Play Contest whose winning plays included Nału by Yana Rusakevich and Viktar Lubiecki [7] (it was produced by V. Shcherban in 2003 on the Small Stage of the Yanka Kupala National Academic Theatre).

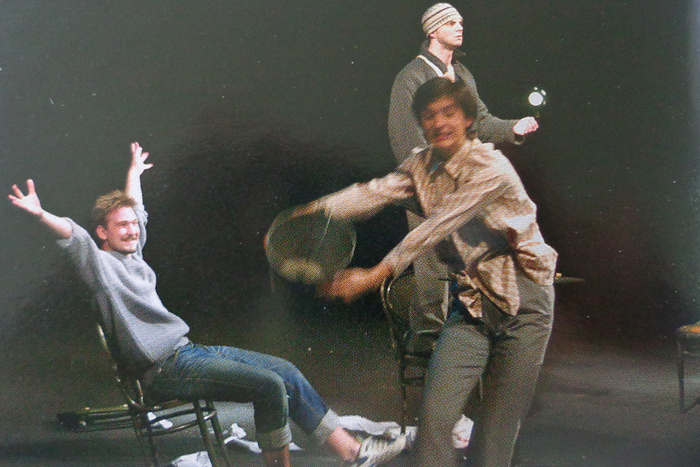

“Wanna be a hamster” by A.Karelin, dir. P.Charlančuk. Theatre On-line project, 2003. Mastactva magazine archive

A number of projects for promoting new plays were proposed by the newly acclaimed playwright Andrej Kurejčyk. In 2003, he announced the establishment of the Centre for Contemporary Drama and Stage Direction at the premises of the Belarusian State Academy of Arts. The Centre formally existed for some time, but has never been put into practice. In 2003, the Theatre On-line project initiated by Kurejčyk was accomplished as part of the Open Format International Festival of Contemporary Theatre (since 2004, the Panorama International Festival of Dramatic Art). Under this project, young stage directors prepared stage readings of contemporary plays they had chosen in just a few days. In spite of the earlier experience of stage readings under German projects and the Theatre of Play project, the Theatre On-line was a discovery for many participants and viewers – draft readings turned into real mini-performances. Later on, the Theatre On-line project became a permanent part of the Panorama festival being absent from its programme only in 2011.

In April 2003, the Centre for Belarusian Drama was open under the auspices of the Belarusian State Institute of Culture Issues which organized discussions on the problems of development of contemporary Belarusian drama and published two drama collections; apart from that, creating a database of plays and playwrights was in the planning stage. In 2005, the Workshop of New Stage Direction project was launched as part of the M.@rt.contact International Youth Theatre Forum in Mahiloŭ, which featured staged readings of plays written by young Belarusian authors including V. Krasoŭski, T. Łamonava, P. Pražko, P. Rasolka, M. Rudkoŭski, and K. Sciešyk. The 2010 workshop dealt in fact entirely with P. Pražko’s works. In 2007, the Centre for Belarusian Drama was established at the National delete Belarusian Drama Theatre. The projects of the Centre gathered young playwrights, directors, actors and Academy of Arts students, and were focused on support and development of contemporary Belarusian play.

A fundamental role in promoting new drama and developing new dramatic genres in Belarus belongs to the Belarus Free Theatre and the Free Theatre International Contemporary Drama Contest (officially announced in 2005).

The contest was a stepping stone for a number of Belarusian authors. The Belarus Free Theatre was probably the first in Belarus to establish a laboratorial cooperation with Belarusian playwrights, that is to stage performances based on purpose-written texts exploring particular themes (e.g. the 2005 project We. Self-Identification and the 2007 performance Childhood Legends). Apart from that, the theatre organized a series of playwright seminars in Minsk participated by foreign experts including, among others, Pavel Rudnev, Maxim Kurochkin and Sir Tom Stoppard. The theatre troupe was among the first to realize the necessity of an alternative theatre methodology for work with new plays and introduced a new understanding of theatricality which is relevant to the present day. The director Vladimir Shcherban claims that his first experience in working with documentary theatre was based on the play Cards ad Two Bottles of Bum-Wine by the Belarusian author P. Rasolka which gave him the task of seeking for adequate stage solutions for rendering the virtuosic language of the play [8].

As can be seen from the above, in the mid 2000s, a burst of activity (the ʻsecond circleʼ) took place in the theatrical space of Belarus: there emerged a new generation of playwrights, the first attempts were made to conduct drama labs, and small dramatic genres (staged readings) were actively utilised. There emerged independent theatre troupes: apart from the Belarus Free Theatre, these were the Kompanija [Company] Theatre headed by Andrej Saŭčanka, Arciom Hudzinovič’s project “View Soul Theatre”; the New Theatre of Aleh Kirejeŭ, Artur Marcirasian and Taciana Trajanovič, the Contemporary Art Theatre of Uładzimer Ušakoŭ, and the D.O.Z.SK.I Modern Choreography Theatre headed by Dzmitry Salesski and Volha Skvarcova.

However, despite the enthusiastic response from critics, these initiatives have failed in general to influence the revision of theatre aesthetics in repertory theatres. The plays of playwrights who had won awards at international contests were unclaimed by repertory theatres, and there was no call for young directors [9]. As far as regards independent theatre troupes, only the very few managed to survive in terms of both finance and aesthetics just as it was ten years before: some of them were forced to deal with exceptionally commercial theatre, some other were seeking ways to survive while not compromising their artistic standards, but the majority of initiatives were just disappearing.

THE THIRD CIRCLE: STARTING OVER?

In such a manner, Belarusian theatre entered 2010s starting from point zero once again. As regards the existing independent projects, those which went on functioning included the InZhest Theatre (in 2012, V. Inozemtsev initiated and held the first Belarussian Forum of Physical and Dance Theatres “PlaStforma Minsk-2013” [10]), the Kompanija Theatre (whose performances had been regularly staged until 2011) and the Contemporary Art Theatre which adopted a commercial strategy. The earlier experience of stage readings, the activity of M. Bartnickaja and the Belarus Free Theatre’s experiments with documentary theatre were—consciously or not—forgotten, which created an impression of lack of any continuity in Belarusian theatre and prospects for its development.

None the less, new independent artistic unions were organized and new initiatives implemented with renewed energy.

In 2010, Evgene Korniag, a young director and choreographer, made a name for himself through gathering young actors and students into the physical and dance theatre project titled “Korniag Theatre”. Within a few years, Korniag staged about a dozen dance and physical performances (Not a Dance, Café Absorption, Play Number 7, Latent Men and others), of which each one was an aesthetic challenge to Belarusian repertory theatre [11]. In autumn of 2010, the amateur theatre movement “Dveri” [The Doors] was launched which, apart from staging performances, holds the regular Amateur Theatre Festival “The Doors”, conducts workshops and publishes The Doors e-almanac [12]. In 2011, Volha Skvarcova and a group of actors left the D.O.Z.SK.I Theatre to found the SKVO’s Dance Company.

The Belarus Free Theatre remains one-of-a-kind – as of today, it is the only continuous theatre project in Belarus which deals with political and social documentary theatre. Following the repression of the December 2010 protests in Minsk (concerning violations at the presidential election in Belarus), the theatre leaders Natalia Kaliada, Nicolai Khalezin and Vladimir Shcherban emigrated from the country. But the theatre, apart from going on tours, continues to regularly give performances in Minsk and to stage new shows [13]. Their 2011 performance A Reply to Kathy Acker: Minsk 2011 received the Award for “Innovation and Outstanding New Writing” at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe 2011. The Fortinbras theatre studio founded at the theatre in 2008 continues its permanent activity.

Within the second wave of the CBD’s activity during the last few years, a series of major projects and drama labs were held (the PONTON German-Belarusian Theatre Meetings, 2010; the MidOst Dramatic Laboratory, 2011; the International Dramatic Laboratory conducted by М. Durnenkov, 2012; the SYPEMEDA International Creative Lab conducted by curators from Switzerland, Germany and Belarus, 2012 and others). The Centre also supported the Studio of Alternative Drama / SAD established in 2011, which is a non-formal association of young Belarusian playwrights, directors and actors with interest in contemporary Belarusian drama founded by S. Ancalevič, D. Bahasłaŭski, V. Krasoŭski and P. Rasolka). In 2011, Kaciaryna Avierkava, the then theatre director of the Mahiloŭ Drama Theatre, initiated the Stage Readings project which included eight presentations of contemporary Belarusian plays. She also staged the play The Host of a Coffee House by Pavał Pražko. It was at the Belarus Free Theatre that his plays Bellywood and Panties were noticed and stage for the first time in Belarus (2006), but The Host of a Coffee House was the first full-fledged production of a Pražko play on the stage of a repertory theatre [13] . (Another premiere of The Host of a Coffee House took place in 2013 in Minsk as an independent initiative, the performance was directed by Taciana Arcimovič). In 2012, the independent information theatre portal ArtAktivist.Theatre was launched. In 2013, the “зЕрне” [Ziernie] Performative Practices Platform made its appearance. It is to serve as a basis for writing a history of contemporary Belarusian theatre, forming a library of new play, and conducting workshops and educational seminars.

Concluding, one can state that yet another wave of activity (the ʻthird circleʼ) has been observed recently on the part of both independent initiatives and state-run theatre. A definite breakthrough – which clearly resulted from the alternative theatres’ activities – was activation of the CBD as well as adding new plays to the repertories of state-run theatres (apart from Pražko’s play being produced in Mahiloŭ in 2013, some state-owned theatres, for example, are preparing premieres based on D. Bahaslaŭski’s plays). And lastly, a whole block of the International Theatre Forum TEART, held in 2012, deals with Belarusian drama.

Authorised translation from Russian by Andrij Saweneć

Tania Arcimovič, 2013

[1] Галковская, Г. Л. Студийные театры Беларуси 1980–1990 годов. — Минск: Белорусская государственная академия искусств, 2005. — 152 с. / H. Hałkoŭskaja, Studiynye teatry Belarusi 1980–1990 godov. Minsk: Belorusskaya gosudarstvennaya akademiya, 2005. — p. 152.[2] The name of the studio is based on a word play of the Belarusian дзея (ʻactʼ) and дзе я? (Where am I?) – translator’s note.

[3] The Scotsman daily newspaper, for example, gave four stars to Truchan’s production of the play The Devil and the Old Woman by F. Alachnović (1995) and five stars to F. Alachnović’s Ghost (1996) and Collapse based on Shakespeare’s works (1997).

[4] Кавалёў, С. Новая беларуская драматургія / С. Кавалёў // Мастацтва. — 2001. — № 1. — С. 14–16. / S. Kavaloŭ. Novaja belaruskaja dramaturhija, “Mastactva” 2001, no. 1, pp. 14–16.

[5] Ратабальская, Т. Беларуска-нямецкія тэатральныя сувязі / Т. Ратабальская // Мастацтва. — 1998. — № 12. — С. 35–38. / T. Ratabalskaja, Belaruska-niamieckija teatralnyja suviazi, “Mastactva” 1998, no. 12, pp. 35–38.

[6] Ганчароў, А. Беларускі тэатр: ілюзія жыцця ці прывід поспеху? Круглы стол “Культуры” / А. Ганчароў // Культура. — С. 9–10, 15–16. / Hančaroŭ, Belaruski teatr: iluzija zhytsia сi pryvid pospiekhu? Kruhly stol “Kultury”, “Kultura” 2005, no. 5, pp. 9–10, 15–16.

[7] At the time, Yana Rusakevich worked as an actor at the National Academic Janka Kupala Theatre. After she started her cooperation with the Belarus Free Theatre, she was dismissed from the Kupala theatre (as well as Vladimir Shcherban who was a stage director there). Today, Yana is a lead actor of the Belarus Free Theatre.

[8] Щербань, В. In between: опыты прочтения [Электронный ресурс]. — Новая Эўропа. — Минск, 2011. — Режим доступа: http://n-europe.eu/tables/2011/12/07/between_opyty_prochteniya. / Shcherban V., In between: opyty prochteniya, “Novaya Europa”, Minsk 2011. Available at http://n-europe.eu/tables/2011/12/07/between_opyty_prochteniya.

[9] The young directors who made name for themselves in the mid 2000s include Kaciaryna Aharodnikava, Michaił Łašycki, Andrej Saućanka, Pavał Charłančuk, and Vladimir Shcherban. Of all the mentioned, only Shcherban is now a fulfilled director working at the Belarus Free Theatre. The rest, even if they were occasionally invited to direct a performance on the stage of a state-run theatre, did not develop such a collaboration and basically disappeared from the theatrical map of Belarus. As a result, one of the key problems of today’s Belarusian theatre is the absence of the middle-generation link, which has a negative impact on the theatrical process.

[10] Артимович, Т. “PlastForma-Минск-2013”: на плечах одиночек [Электронный ресурс]. — Новая Эўропа. — Минск, 2013. — Режим доступа: http://n-europe.eu/article/2013/02/22/plastforma_minsk_2013_na_plechakh_odinochek / Arcimovič T., “PlaStforma-Minsk-2013”: na plechakh odinochek. “Novaya Europa”, Minsk 2013. Available at http://n-europe.eu/article/2013/02/22/plastforma_minsk_2013_na_plechakh_odinochek

[11] While studying contemporary world theatre and dance practices, Evgenij Korniag developed his own style and physical language which make his performances unique on a national scale.

12] Available at dverifest.org/almanah/. As of today, eight issues of the almanac have been published.

[13] In 2012, the premiere of K. Sciešyk’s play Near & Dear Ones directed by V. Shcherban took place. The rehearsals of the performance were held via Skype.

[14] In 2010, V.Anisienka put P. Pražko’s play When the War is Over on the stage of the RTBD Theatre. But the playwright himself considers this play an ʻoddʼ one as it does not comply with his artistic aims and tasks which have already become his signature mark.

On the cover // The Host of a Coffee House by Pavał Pražko, dir. T.Arcimovič.

Opinions of authors do not always reflect the views of editors. If you note any errors, please contact us right away.